SEIKI – AN AMERICAN QUARTERBACK

By Hugh Wyatt

PROLOGUE

I first heard of Seiki Murono when I was coaching a minor league

football team in Hagerstown, Maryland, in the early 1970s.

I'd seen his name on the statistic sheets of another minor league, and

by chance I’d heard a friend named John Winterburn, a native of

Vineland, New Jersey, talk about a great quarterback from his area

(“South Jersey,” as its natives call it) - named Seiki Murono.

He was Japanese-American. There haven’t been that many

Japanese-American football players.

John pronounced his first name “SEE-key.” I’ve since learned,

from Seiki himself, that it’s properly pronounced “SAY-key.”

But that was that, for another 45 years or so, until the day I decided,

for no particular reason, to do a little research on that

Japanese-American quarterback.

First, I found a Seiki Murono who lived in San Francisco, where he was

actively involved in business as an associate with an international

executive search firm.

Further research connected him to Franklin and Marshall College, where,

it turned out, he’d played football.

I’d found my man.

I managed to contact him by email, simply in hopes of exchanging

stories of minor league football, but instead I managed to stumble onto

an amazing life story - an inspiring American story. As a history major

in college, it didn’t take me long to figure out that since he was just

a few years younger than I, he almost certainly had experienced

firsthand the World War II internment of Japanese-Americans.

He confirmed this, and referred me to a book entitled “Connecticut

Gridiron,” a history of Northeastern minor-league and

semi-professional football by William Ryczek, with whom he’d shared

much of his family’s story.

And he sent me the text of his father’s post-war, post-internment

testimony to a Congressional committee.

As I read, I realized that as bad as the internment of

Japanese-Americans was, the injustice inflicted on the Murono family

was almost beyond belief. They weren’t Japanese-Americans at

all. They were Japanese-Peruvians. They had been taken from

their home and their business in Peru, and removed to the United

States, their lives uprooted – for what?

Whatever pretext there may have been to justify the internment by the

US government of Japanese-Americans, there was no possible way to

argue that the Muronos, who had never set foot on American soil until

being brought here and incarcerated, were a threat to American security.

What sort of people must Seiki’s parents have been, I wondered, to have

suffered the injustices and indignities of the internment experience,

but then to have resigned themselves to their fate and dedicated their

efforts to ensuring that their children would achieve success as

Americans - to have put bitterness aside and become, in time, American

citizens themselves?

Like so many biographers, I felt a sense of accompanying Seiki on

his journey, checking with him from time to time as if to say, “Did I

really see what I think I saw?”

The “journey” took me to Peru, to internment camps, to his hometown of

Seabrook, New Jersey, and to his college, Franklin and Marshall, in

Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Coincidentally, one of the first college games

I ever saw took place at Franklin and Marshall, in 1950. The father of

one of my friends was assigned to officiate a game there, and he took

us two kids along. An additional coincidence was learning that

Ken Twiford, a high school teammate of mine, was an assistant at F

& M when Seiki Murono played there.

In the process, I learned much of the life story of a very remarkable

person, Seiki Murono; but in learning about him, I also learned

far more than I ever knew about the Japanese internment experience.

And I was reminded, once again, that when people come to America, often

under the most unbelievably difficult of circumstances, their

decision to “become American” – to work hard and ensure that their

children get educations - enriches us all.

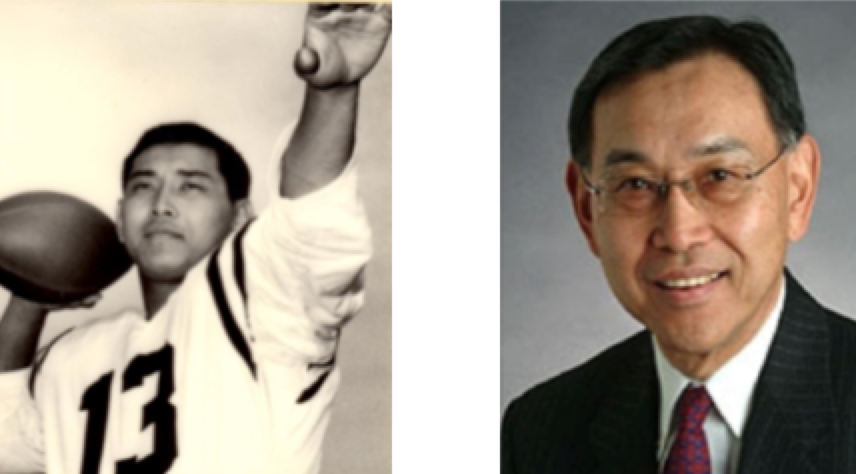

THE QUARTERBACK

It was late Saturday afternoon, November 13, 1965. Muhlenberg

College had just gone down to defeat, 49-26, at the hands of Franklin

and Marshall, but despite the sting of the loss, the Muhlenberg

coach marveled at the performance of F & M’s quarterback, Seiki

Murono.

“Murono is the best quarterback we’ve seen in the past two years,” he

told Jim Riley of the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Intelligencer Journal.

“No, I take that back. He’s the best football player we’ve seen

in two years… He does everything well and his leadership is fantastic.”

And that was despite his having seen Seiki Mureno play just one

half of football. With a big halftime lead, F & M coach

George Storck had chosen in the interests of sportsmanship to rest most

of his starters, including Murono, in the second half.

In that one half, though, Murono, a senior from Seabrook, New

Jersey, had accounted for 250 yards of total offense - 131 yards

rushing and 119 yards passing.

In another week, Seiki Murono would conclude an outstanding

career at Franklin and Marshall, one in which he had set numerous

school records for passing, punting and total offense, and one in which

he had led a team that had been 1-7 his sophomore year – and had won a

total of just four games in four years – to a perfect 8-0 record in his

junior season and a 12-4 mark in his final two seasons.

In another six months, Seiki Murono would graduate from Franklin

and Marshall, a prestigious liberal arts college, and go on to a long

and successful career in international banking.

In the meantime, few people, including his own teammates, had any idea

that he had been making history as the only Japanese-American born in a

World War II internment camp to play college football.

Twenty-two years earlier, Seiki Murono’s father, Ginzo Murono, had

arrived in the United States from Peru. His immigration was

anything but voluntary.

Late on the evening of January 6, 1943, Mr. Murono, a Peruvian of

Japanese descent, the owner of two sporting goods stores with a wife

and two small children, was approached at the door of his home in Lima

by a Peruvian police officer and told, “by order of the United States

government, you are hereby arrested.” Thus ended his life in Peru

and began nearly four years of incarceration.

(The shameful story of the internment of Japanese and

Japanese-Americans living in the United States at the outbreak of World

War II is now well known. Almost unknown, though, and never fully

explained by the United States government, was the removal of Japanese

from Latin-American countries, mainly Peru, for internment here. Author

Thomas Connell, in his 2002 book, “America's Japanese Hostages,”

suggests it was part of a goal of “a Japanese-free hemisphere.”)

Mr. Murono was taken first to a Lima police station, where along with

60 or so other Japanese men he spent the night in a room so small that

it was impossible for any of them to lie down and sleep.

The next morning, the men were loaded onto three open-bed trucks and

driven off. Their journey, to a destination unknown to them, took

two days. It was summer in the southern hemisphere and the

sun beat down fiercely. No food was provided. “The trip,” Mr.

Murono would recall later, “was a terrible one.”

“It was during this trip,” he would later tell a United States

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment, “that I began to feel

the complete separation from the peaceful family and social life I had

in Peru. Without committing any wrong, and without even a

hearing, our individual rights had been taken from us.”

On reaching their destination, a seaport in the north, they were

loaded onto a ship (“the bottom of the ship,” he would recall)

and after a three weeks-long voyage, during which time the passengers

were fed just two meals a day, they arrived in San Francisco.

Without a visa – his had been confiscated by the Peruvian police

- Mr, Murono was considered an illegal alien, and was shipped by

train to Kenedy Alien Detention Camp, in Kenedy, Texas, about 50 miles

southeast of San Antonio.

In June, after six months at Kenedy, Mr. Murono was transferred to

another internment camp in Crystal City, Texas. His wife, in the

meantime, had applied through the Spanish Embassy in Lima for

admission to the United States, and when her request was granted, she

and the Muronos’ two children, three-year old daughter Toyoko and

one-year-old son Eisuke, boarded a ship bound for New Orleans. The

voyage, via the Panama Canal, took two weeks. There

followed a two-day train ride to Crystal City, where in July, after

seven months’ separation, the Murono family was reunited.

Crystal City, about 120 miles southwest of San Antonio and not far

from the Rio Grande, was primarily for internees with families.

There were as many as 1,000 Germans, and a small number of Italians,

but the camp’s population was mostly Japanese, some 3,000 of them,

roughly half from the United States and half from Peru.

Nearly a year after their reunion in Crystal City, the Muronos welcomed

their third child, a son named Seiki. It was June 6, 1944.

D-Day.

At Crystal City, the internees were paid 10 cents an hour for their

work. Although kept under guard and behind barbed wire, they were given

a remarkable amount of freedom within the camp itself.

The internees developed and ran what Mr. Murono recalled as “a rather

efficient society,” electing their own officials and managing their own

schools, their own post office, their own stores, and such essential

services as garbage collection. They had newspapers, amateur theaters

and sports teams. They had freedom of worship and the right to hold

meetings.

The resourcefulness and resilience of a people suddenly and

involuntarily yanked away from everything they owned, from familiar

faces, places and things, and then, after incarceration, to make the

best of such harsh circumstances, is almost incomprehensibly noble.

In August, 1945, more than two years after the Muronos had been

reunited in Crystal City, “a long siren sounded,” Mr. Murono

recalled. “The war was over and peace had finally come.”

But while World War II may have ended, that did not mean freedom for

the Muronos. Like all Japanese Peruvians sent to the US,

they had lost everything. There was no home to return to, no business

to resume.

And they were stateless. Their passports had been taken away by

the Peruvian government, and in the United States they remained

"illegal aliens.”

Finally, in August of 1946, a year after the war ended, so also did the

Muronos’ four years of incarceration. They left Crystal City for a new

life, in a strange and faraway place called Seabrook, New Jersey.

Seabrook, New Jersey was the home of Seabrook Farms, a giant

producer of vegetables, processing and packing peas, beans,

asparagus and other vegetables and fruits grown on its 6,000

acres of farmland in rural southern New Jersey about five miles north

of the city of Bridgeton.

Charles Franklin (C.F.) Seabrook had bought his father’s farm in

1912, and by the outbreak of World War II, through his pioneering

work in frozen food processing and his application of modern industrial

production techniques to farming, had built Seabrook Farms into

what Life Magazine called ''The Biggest Vegetable Company on Earth.”

The largest single farm in New Jersey, Seabrook Farms was 9 square

miles in size, with 30 miles of paved roads. It had its own giant

packing plant with enough railroad siding to allow the loading of 30

freight cars at a time. At peak production it employed 4,000

workers, and shipped 100 million pounds of vegetables a year.

With the war effort requiring enormous amounts of food, Seabrook Farms

became the major supplier of vegetables to the military.

But with most able-bodied men either in the service or employed in

well-paying “war work,” it was difficult to find workers.

Seabrook Farms even employed hundreds of Italian immigrants and German

prisoners of war, but even so, under constant pressure to fill

government contracts, it faced a chronic labor shortage.

In 1943, partly to ease the problems of employers such as Seabrook, the

US government began to permit many Japanese internees to

leave the camps, provided they could pass a loyalty test and find jobs.

They weren’t totally free to move about, though – their every move had

to be approved by a government agency called the WRA – the War

Relocation Authority. (And until December of 1944, the West Coast

states remained off-limits to any former internees.)

Seabrook’s connection to the internment camps began in December of

1943. A recently-liberated former internee named George Sakamoto,

who had left his family behind at a camp in Colorado while he searched

for a place to resettle, happened to be riding on a train to New York

when he came across an article in Reader’s Digest about Seabrook Farms.

Seabrook needed workers, he read, and with the permission of the

WRA, he made his way to South Jersey to investigate.

Most of the other workers at Seabrook had never seen a Japanese person

before, he recalled, and "they were curious as hell," Mr. Sakamoto told

the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Michael Vitez in June, 1988. “They

would come up and say, 'Hey, you don't look like the Japanese we see in

the papers.' They were curious, but friendly."

He decided to stay, and went to work at 49 cents an hour. Seeing

him at work gave C. F. Seabrook an idea. Where others saw

internment camps, he saw workers - and he set in motion a

plan to solve his labor shortage with former internees.

Seabrook’s employment manager was commissioned to visit camps and

recruit workers. “Come and see for yourself,” he told internees at an

Arkansas internment camp in April of 1944. “We’ll pay your

transportation.”

Shortly after, a delegation of three representatives from the camp

visited Seabrook, talking with workers and local business people and

government officials to assess how Japanese-Americans would be accepted.

Their report upon their return must have been favorable, because

shortly afterward, families began to leave for Seabrook, and in time,

more than 300 families from that one camp in Arkansas would accept

Seabrook’s offer.

The government paid their train fare to Seabrook, and the company

agreed to provide lodging, lunch, and utilities. To house them,

Seabrook had managed to get the federal government to build a large

number of small concrete block homes. For their part, the

Japanese-Americans were required to work in Seabrook's processing plant

for at least six months.

Eventually, following the initial wave of workers from Arkansas,

families began to arrive in Seabrook from internment camps in Arizona,

Colorado, Utah and Wyoming.

"They were put to work as soon as they got here, as soon as they

changed their shoes," George Sakamoto recalled. "You got here in the

afternoon and went to work on the night shift."

The work was hard and long - 12-hour shifts – and the pay was low -

anywhere from 35 to 50 cents an hour. During peak harvest periods they

worked seven days a week.

Essentially, Seabrook was a company town. Seabrook Farms owned

the houses and the only store in town. The nearest other store was in

Bridgeton, five miles away, but to people with no cars, not to mention

wartime rationing of gasoline, it might as well have been 50 miles.

The workers nevertheless made the best of their circumstances.

"Some people might say C.F. was an opportunist, taking advantage of our

situation," said George Sakamoto. "But what the hell. We were in bad

shape, we needed a chance. And for people in our situation, it was hard

to say no."

The Seabrook that Seiki Murono grew up in was a remarkably diverse

community. The German and Italian prisoners of war had left

Seabrook once the war ended, their places taken by Peruvian-Japanese

like the Muronos, and by Estonians, who had fled their country when the

Russians swept through Eastern Europe following the war. There

was no segregation by race or nationality. The various groups were

integrated and, in Seiki’s words, “lived harmoniously together.”

The Muronos lived in a one-room house, with a coal burning stove for

heat. There was no bathroom. “There was a communal bathroom and

shower facility which was used by all the residents of the complex,”

Seiki recalled. “I remember how terrible it was to have to walk

to and from the bath facility during our frigid winters.”

Because Mr. Murono’s income wasn’t sufficient to support the family,

Mrs. Murono had to go to work, too, which meant that two-year-old Seiki

was sent to a child care center run for the families of Seabrook’s

workers.

Until he entered Seabrook Elementary School, Seiki Murono spoke no

English. At school, the Japanese and Estonian children were taught

English as a second language. “It was quite a struggle at first,” Seiki

now recalls, “since my parents, who knew almost no English, spoke

only Japanese at home. It was a priority for me to learn English

so that I could fit in.”

Seiki’s parents never studied English, Seiki says, but they became

proficient, “through day-to-day living and watching TV.”

Looking back, Seiki Murono recalls a childhood that could have been

spent almost any place in America… … “Opening day of trout fishing

season in April at Pennsgrove Lake and Shaws Mill Pond near

Cedarville… Waiting to hear the jingle from the Mr. Softee truck

so I could buy my root beer float… The Boy Scout troop under the

leadership of Vernon Ichisaka.” (Numerous Japanese-American children

from Seabrook became Eagle scouts.)

Seabrook’s kids played kick the can and Red Rover… And marbles (“our

earliest introduction to gambling, because whatever you won, you got to

keep,” recalled one of Seiki’s contemporaries).

And they also took part in activities unique to a Japanese community –

playing a game called jin-tori, said to be something like capture the

flag, and making mochi, a Japanese treat.

As Seiki grew older, there were pickup games of all sports.

There was basketball on the outdoor court at the elementary school.

There was baseball, which, as one schoolmate of Seiki’s recalled,

meant “sharing baseball gloves after each inning because not

everyone owned one… a couple of bats, and an adhesive-taped ball that

had to last the whole game... the team at bat designating one of its

own players to call balls and strikes and each team keeping its own

score, an arrangement that produced surprisingly few arguments… base

runners stealing second base without sliding, to avoid tearing their

pants or skinning their knees on the rock-hard ground.

And there was football. Seiki recalled “being chased away by Mr.

Miller, the Seabrook School custodian, when we were playing football on

the lawn in front of the school.” Added a schoolmate, “When we didn’t

see his pickup truck parked by the school, we would play football. As

we played, we would keep an eye out for his pickup coming down Highway

77. When someone saw it we would all scatter.”

Not that it was all play. Not by any means. “I don't remember

ever taking a family vacation,” Seiki said. “From the time

each of the children was 13 (the minimum working age at the time), we

all had summer jobs.” He remembers picking beans, “making 35 cents a

basket, and chasing rabbits to break up the monotony.”

And there was schoolwork. In keeping with the emphasis on

education and the desire to excel academically characteristic of

Asian-Americans in general, Seiki says, “My parents stressed

education and wanted all three of us to get a college education. We

were encouraged to study hard and we did this mostly at home since our

community did not have a library.”

Whether at school or at play, though, Seiki said, he and his brother

strove to excel.

“My brother and I embraced the American ethic of competing to succeed,”

he says. “We both wanted to excel both academically and athletically to

prove we belonged.”

In the fall of 1958, Seiki and his classmates from Seabrook Elementary

moved on to high school in nearby Bridgeton, a city of 20,000 or

so, with one large high school. Bridgeton High School was itself

quite diverse, with a fairly large African-American population, and the

Japanese-American kids from Seabrook had no trouble fitting in.

“We were very well accepted,” Seiki remembered. “Most of

the Japanese kids excelled in school and participated in athletics,

mostly basketball, baseball and football.”

At Bridgeton, Seiki played all three of those sports.

He almost didn’t play football. As a freshman, he weighed just 119

pounds, and thought seriously about quitting. “I questioned

whether or not I could match up physically with some guys who were 100

pounds heavier than that,” he said. “I decided to hang in there, and

was glad I did.”

As a quarterback, he especially admired the Baltimore Colts’ Johnny

Unitas, “I didn't view him as a gifted athlete,” he said, “but someone

who made the most out of what he was given. He was steady,

consistent and reliable, and someone who almost always delivered in the

clutch.”

In his senior year, in order to make better use of Seiki’s talents as a

runner and a passer, his coach, Barney Fisher, installed a single-wing

attack, with Seiki as tailback doing most of the running and passing.

Bridgeton won the South Jersey Group IV (largest classification)

football championship, and Seiki was named first team all-conference

quarterback and the conference MVP.

In the spring, with Seiki at second base, the Bridgeton High baseball

team also won the South Jersey Group IV championship.

He was co-captain of both the football and baseball teams, and the

president of his senior class, and he graduated with honors.

And then it was off to college. Remarkably, nearly all of the Japanese

students in his class at Bridgeton went on to college, to schools such

as Rutgers, Tufts, Yale, Columbia, Brown, Dickinson, Delaware,

Bucknell, West Virginia Wesleyan, Trenton State (Now College of New

Jersey), Ryder, Drexel, and Penn.

For Seiki, the choice was Franklin and Marshall, a small,

well-respected liberal arts college in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

Partly, he admitted, he chose F & M because his brother, Eisuke,

was a sophomore there and a member of the football team. (Eisuke

had chosen F & M because of its strong science department.) Mainly,

though, Seiki chose F & M “because it was an excellent liberal arts

college where I could play football and baseball and get a high quality

education.”

When Seiki arrived on campus in the fall of 1962, he wasn’t

entirely unknown. His brother had already established himself as the

starting fullback on the varsity football squad. And his coach at

Bridgeton, Barney Fisher, had made sure to let the F & M

coaches know what sort of athlete they were getting in Seiki.

On the freshman squad (NCAA rules at the time prohibited freshmen from

playing varsity football), Seiki played both quarterback and

defensive back. While the varsity team struggled and went

winless, the freshmen team, playing an abbreviated

schedule, finished with an encouraging 2-1 record.

As he entered his sophomore year, the F & M Diplomats had won just

three varsity games in three years. But change was under way - a

new coach, a West Point graduate named George Storck, had come on

board, and he quickly saw what a talent he had in his sophomore

quarterback, Seiki Murono. With new substitution rules allowing

Seiki to concentrate on offense; Storck installed a sprint-out,

run-pass-option offense to take full advantage of his quarterback’s

skills.

Unfortunately, a shoulder separation suffered in an early game hampered

Seiki’s play for most of the season, and F & M limped home with

just one win.

His injury not only delivered a setback to the coach’s rebuilding plan,

but also cut short Seiki’s one season of playing on the same college

team as his brother, by then the team co-captain. Ironically, Eisuke’s

season was also limited by injury.

The 1964 season began with high hopes. In pre-season scrimmages,

then commonplace among colleges, the Diplomats held their own against

Lebanon Valley and Upsala. An impressed Coach Storck called the

performances “the best football I have seen Franklin and Marshall play.”

If they needed further reason for optimism as they prepared for the

season opener in Baltimore against Johns Hopkins, the school newspaper

pointed out that with junior Seiki Murono set to start at quarterback,

it would mark the first time since 1959 that F & M had not opened

the season with an untested sophomore at that key position.

With Seiki completing 17 of 23 passes for 181 yards, the Diplomats

ended a 6-game losing streak, defeating Hopkins, 21-6.

Swarthmore was next. Although F & M led only 7-6 going into

the fourth quarter, they scored twice to win, 21-12. Seiki threw only

five passes, but he completed four for 46 yards, and he ran for

two touchdowns.

The next week in a downpour, F & M struggled to pull out a

win over Dickinson by the unlikely score of 6-5. Just two minutes

into the game, Seiki was tackled in the end zone for a safety, and a

field goal shortly afterward gave Dickinson an unusual 5-0 lead.

Hampered offensively by the weather, Seiki threw for just 109 yards,

but one of his 13 completions was the winner - a 33-yard touchdown pass

late in the fourth quarter. The win made the Diplomats 3-0 for the

first time since 1953.

With win number four over Carnegie Tech, 18-14, the Diplomats equaled

the total number of wins by the school in the previous four

years. Although down 14-10 after 3 quarters, the Diplomats

put together a late scoring drive, with Seiki sneaking over from the 1

and then passing for the two-point conversion.

Haverford was next, and the Fords led 6-0 going into the fourth

quarter, but Seiki engineered two touchdown drives in the final 10

minutes to pull out a 14-6 win.

Pennsylvania Military (now Widener University) was the third straight

opponent to take the game down to the wire, scoring with only a

minute to play to take a 17-13 lead. But Seiki drove the

Diplomats 60 yards in less than a minute, scoring from the one

with seconds left to give F & M the 19-17 win. He

was 13 of 21 for 237 yards passing.

Against Muhlenberg, in what the school newspaper called “The most

brilliant performance of his intercollegiate career,” Seiki completed

24 of 35, passing for 320 yards and three touchdowns and running

for a fourth, as F & M triumphed, 29-20,

Ursinus was the final opponent, and the Bears went down, 20-6 as

Seiki completed 18 of 25 for 130 yards, and ran for a touchdown.

The Franklin and Marshall Diplomats , 8-0, had finished a season

unbeaten for the first time since 1950, and for only the second time in

the school’s long history of football dating back to 1887.

The jubilant home crowd, as had become its custom throughout the

season, tore down the goal posts, and then followed an impromptu

motorcade, taking the coaches and the players on a “triumphant march,”

in the school newspaper’s words, through downtown Lancaster.

It had been quite a season for Seiki Murono. He

accounted for 1150 yards of total offense, completing 108 of 180 pass

attempts for 1021 yards and six touchdowns, and rushing 90 times for

129 yards and 7 touchdowns. He led his league’s division in

passing, punting and total offense.

The honors poured in.

In recognition of his efforts, Seiki was honored by Philadelphia’s

Maxwell Football Club.

He became the first F & M player since 1960 to be named to the

all-conference team, and was named the conference MVP.

“He’s every bit deserving of this honor,” Coach Storck told the F &

M College Reporter. “My contention at the beginning of the season that

Seiki was the finest quarterback in the conference has certainly been

proven. Moreover, he’s withstood an awful lot of pressure and

he’s come through. He’s modest and accepts the limelight as a

team member, not a star. His humble approach makes him

greater.”

Seiki played baseball in the spring of his junior year, and after a

summer working as a Coca-Cola route salesman in South Jersey, as he’d

done throughout his college career, he returned to F & M with high

hopes for his senior season.

Elected co-captain, his importance to the team was summed up by his

coach’s referring to him in Sports Illustrated’s pre-season issue as

“the offense.”

Alas, although Seiki had another good year offensively, the Diplomats

were unable to duplicate the magic of the previous season, and

finished a somewhat disappointing 4-4.

Nevertheless, for the second consecutive season, Seiki was named

the league’s Most Valuable Player. He passed for 888 yards and

nine touchdowns, and ran for 363 yards and four touchdowns. In

addition, he punted 31 times for a 34.4 yard average.

In what was essentially a two-year career, Seiki Murono accounted for

2671 yards and 29 touchdowns on 552 plays, and punted 120 times for

4305 yards.

He was accorded an honor seldom conferred on a small college player

when he was named second team All-Pennsylvania (one of his teammates: a

Pitt lineman named Marty Schottenheimer, who would go on to fame as an

NFL head coach).

And in his home state of New Jersey, he was named the Brooks-Irvine

Memorial Football Club’s College Player of the Year, recognizing him as

the outstanding college football player from South Jersey.

(Winners over the years have included such college All-Americans

as Penn State’s Franco Harris, Lydell Mitchell and Greg

Buttle, Nebraska’s Mike Rozier and Irving Fryar, and Wisconsin’s

Ron Dayne. Rozier and Dayne won Heisman Trophies; Rozier, Harris,

Mitchell and Fryar all went on to make Pro Bowl appearances.)

As well as being co-captain of both the football and baseball teams, he

was also President of Franklin and Marshall's Black Pyramid Senior

Honor Society, whose members, according to its site, “are chosen

through a rigorous screening of academic intellectuality,

extracurricular activities, and community involvement.”

He graduated with honors in business management as his proud parents

and his paternal grandmother, who flew in from Kyoto, Japan looked on

with pride.

And then it was on to business school at the American University in

Washington, D.C. where he would earn an MBA degree, specializing in

international finance.

Although his studies went well, he missed football, and after a

year away from the game, he signed a contract to play for the

Westchester (New York) Bulls of the Atlantic Coast Football

League. The Bulls were a minor league affiliate of the New York

Giants and the two head coaches for whom Seiki played were former

Giants Alan Webb and Joe Walton. (Alan Webb’s appointment made

him the first black head coach of a professional football team at any

level. Joe Walton would later become head coach of the New York Jets

from 1983-1989.)

In the 1960s and early 1970s, there actually was such a thing as minor

league professional football, and the quality of play was quite high.

In 1967, when Seiki signed to play, there were just 24 major league

professional football teams - 15 in the National Football League and

nine in the American Football League - instead of today’s

32. And those 24 teams carried rosters of just 40 men each, which

meant there was a total of just 960 jobs in major league professional

football. By contrast, today’s 32-team NFL has 53-man rosters,

providing 1696 job opportunities for players. In other words, in

1967 there were more than than 700 football players good enough

by today’s standards to be on an NFL roster, but without a team to play

for. Many of those “unemployed” chose to remain active, playing

the game they knew and loved, on minor league teams.

Having been cut by NFL or AFL teams, they played on in hopes of

getting another chance at the big time. Few of them made much

money doing so. Most of them had outside jobs, Many had families.

Many were students. Whatever their reason for playing, at heart

they were all playing for fun, postponing the inevitable day when

they’d no longer be able to play a sport they’d loved since they were

kids.

The best of them found their way to the Atlantic Coast Football League,

whose best (and best-financed) teams were in Hartford and Bridgeport,

Connecticut and Pottstown, Pennsylvania.

From the ACFL, some did make it to the NFL. There was Bob Tucker, a

tight end from Bloomsburg State who played for the Pottstown Firebirds

before getting his chance with the New York Giants. He took advantage

of it and lasted for 11 seasons in the NFL.

Marv Hubbard signed with the Hartford Knights out of Colgate, and wound

up an All-Pro running back with the Oakland Raiders.

Chuck Mercein, a running back from Yale, was drafted by the New York

Giants and sent down for two games to the Westchester Bulls before

being cut. And then, in mid-season, Green Bay’s Vince Lombardi signed

him, and his running on the “frozen tundra” of Green Bay was a

key factor in the Packers’1967 Ice Bowl victory over the Dallas

Cowboys..

The success of many minor league players extended well beyond their

playing days.

Bob Brodhead, a Duke graduate, was twice named All-Continental League

quarterback for the Philadelphia Bulldogs, and went on to be Athletic

Director at LSU.

Gary Van Galder, captain of Stanford’s 1957 team, was a student

at Yale medical school in 1962 when he was coaxed into playing for the

Ansonia (Connecticut) Black Knights.

Don Abbey, a big fullback/linebacker from Penn State, played briefly

for the Hartford Knights in 1970 before embarking on a career in

commercial real estate in Southern California that would make him one

of America’s wealthiest men.

Jack Dolbin, an all-ACC running back at Wake Forest, played minor

league football with the Pottstown Firebirds and the Schuylkill Coal

Crackers of the Seaboard League, and spent a year with the Chicago Fire

of the World Football League before signing with the Denver Broncos. He

started 67 games for the Broncos, and was the leading receiver in Super

Bowl XII. He’s now Dr. Jack Dolbin, owner of a sports and

rehabilitation center in Pottsville, Pennsylvania.

Seiki Murono’s balancing act between the demands of his career and his

love of football was not an uncommon one at the time, especially for

quarterbacks.

Bob Brodhead, in his book, “Sacked,” told how he was forced to juggle

careers when his team, the Cleveland Bulldogs of the United Football

League, first moved to Canton, Ohio, then was acquired by a group of

Philadelphia businessmen, with plans to play in the newly-formed

Continental Football League.

The Philadelphia group wanted Brodhead, who had just been named MVP of

the United Football League, as part of the deal.

The problem, he wrote, was that “I couldn’t afford to quit my job

in Cleveland and move to Philly for what they paid me to play

football.”

When the owners proposed flying him in for practice two nights a week,

and then to wherever the team happened to be playing on the weekend, he

accepted their offer.

As he described his routine, “Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays during

the season saw me hard at work as general manager of A. J. Gates

Company, a Cleveland-based materials-handling firm. Late

Wednesday afternoons, I’d hop a plane for the fifty-minute flight to

Philadelphia. I’d practice on Wednesday and Thursday evenings,

sleeping at the Germantown YMCA, fly home for work on Fridays, then

join the team on Saturdays in cities from Toronto, Canada to Orlando,

Florida.”

Seiki Murono’s arrangement with the Westchester Bulls was similar: his

school work meant frequent travel between Washington and New

York. “Playing for the Bulls while getting my MBA,” he

recalled, “required taking the Eastern Airlines shuttle between

DC and New York 3-4 times a week for both practice and games. It

was a crazy thing to do now that I look back, but at the time, it was

exciting and fun.”

The following spring, he was tempted briefly to stray from his career

path. His college coach, George Storck, had resigned his position at F

& M to return to West Point as freshman football coach and

associate athletic director, and he asked if Seiki might be

interested in joining him as an assistant coach. But Seiki, about to

graduate from American with his MBA degree, decided instead to enter

Chase Manhattan Bank’s management training program in New York.

Meanwhile, he continued to play minor league football.

Surprisingly, he had the blessing of his superiors at Chase Manhattan.

“They loved it,” he told William Ryczek, in “Connecticut

Gridiron.” “They put articles in the Chase newsletter. I worked

on the same floor with the person who eventually became president

of the bank, and every Monday he’d say, ‘Well, how did we do this

weekend?’ They loved the fact that I was a professional at the

bank and playing professional football at the same time.”

As with other minor league players, making money was not Seiki’s main

objective. He simply enjoyed playing football, and was realistic

about his chances of playing in the NFL: “I realized that was probably

going to be the pinnacle of my football career,” he said, “and I was

going to play as long as I could, while dedicating most of my energy

and attention to my banking career.”

By 1973, though, the physical toll of football combined with the

increasing responsibilities of his position with Chase Manhattan to

persuade him that it was time to focus on his banking career.

He never looked back.

Although the birth of the World Football League in 1974 created

enticing new opportunities in professional football, he never

considered it. “The WFL was a cut above the Atlantic Coast Football

League,” he says, “And I was realistic about my ability to

compete at that level.”

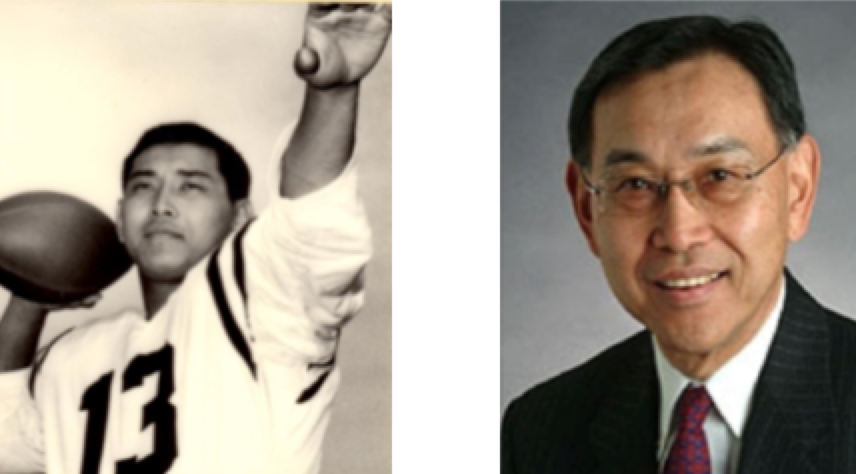

Thus was launched a career with Chase Manhattan that spanned 25 years

(and “3.1 million miles on United Airlines,” he notes), starting

in New York and taking him to increasingly responsible positions in

Singapore, Hong Kong and San Francisco.

In Singapore, he was Southeast Asia Regional Manager for consumer and

private banking in addition to running all of Chase’s Southeast Asia

credit card operations.

In Hong Kong, he was Asia Pacific Area Executive for private

banking, responsible for more than $6 billion in clients’ assets.

In his last position, based in San Francisco, he was Senior Vice

President of The Chase Manhattan Bank, and President of the Chase

Manhattan Trust Company of California.

After retiring from Chase Manhattan in 1995, Seiki became Chairman of

the Board of San Francisco-based Millennium Bank, which was sold in

2000. He currently serves on the board of directors of California

Business Bank, based in Irvine, and Millennium Capital, a

Shanghai-based investment bank.

He also is a Partner in the San Francisco office of Boyden Global

Executive Search, specializing in senior-level financial services

searches.

By any measurement, Seiki Murono represents the fulfillment of the

American dream.

He’s done it the classic American way – through hard work, dedication

and persistence, and with the support of a loving, caring family and

good mentors.

And football, as he will freely admit, has played a key role in his

success.

POSTLOGUE

Looking back at a long and varied career that’s taken him from an

internment camp, to a company town, to a small and selective college,

to athletic success in college and professional sports, to the acme of

international business, Seiki reflects on the factors that helped make

him successful.

From an early age, the sense of “belonging” was a powerful

motivator. “When I was growing up,” Seiki says, “I thought about

being ‘different’ constantly and did whatever I could to be accepted

and excel in everything I did. It was the driving force in my

early years which shaped who and what I became.”

Playing sports, he says, was “huge,” in terms of his overall

development. “I felt most ‘American’,” he said, “When I was

playing sports. It was probably the main reason I chose to

participate in athletics...to assimilate and to gain acceptance.”

Teachers and coaches, football and family have been major forces in his

life…

“My high school English teacher, Mrs. Jane Owen, was very special,” he

says. “She made sure I learned how to speak proper English by

teaching me how to diagram sentences and conjugate verbs. To this

day, I remember and use what she taught me. When I was a senior

in high school, it was she who suggested I consider a career in

international banking. Amazing, since I had no idea what

international banking was!”

Two other important influences were his football coaches – Barney

Fisher at Bridgeton High School, and George Storck at Franklin and

Marshall. “Both,” he said, “were exceptional mentors. from

whom I learned so much about life skills, leadership and being a decent

human being.”

F & M, he says now, “Was a very good choice. I received

a terrific education and had the opportunity to play for a great

football coach. Football - and the positive influence of Coach

Storck - laid the foundation for my career in business.

Playing team sports, especially as a quarterback, taught me leadership

skills and the importance of cooperation and collaboration as keys to

achieving success and reaching objectives.”

But most important of all were his parents.

Other than the abduction of Ginzo Murono and the separation from the

life the Muronos knew in Peru, and other than the fact that

incarceration was their introduction to the United States, the Muronos

were like so many other immigrants to the United States in the manner

in which they worked and sacrificed to give their children

opportunities that they knew they would never have themselves.

At one point they considered moving back back to Peru, Seiki says, but

they chose to remain in the US because they wanted all three of their

children to be educated here, and they thought opportunities would be

better for them here.

“They believed that we could make it,” Seiki says. “And the key was for

all of us to receive a good education. They made tremendous

sacrifices so that we could achieve this objective.”

In return, he said, “We wanted to make our parents proud and bring them

honor for the sacrifices they made.”

The Muronos must surely have felt honored and repaid by the

accomplishments of their children.

In addition to Seiki, older brother Eisuke earned his PhD in

endocrinology and was a senior scientist for the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention, and taught at the medical schools at the

University of South Carolina and at West Virginia University.

Older sister Toyoko graduated from Columbia University. While

still an undergraduate, she began working in the Foreign Admissions

Office, and continued to work there after graduation, overseeing

applications from foreign students hoping to attend Columbia.

It is remarkable to think of what the Muronos did for the sake of their

children. Dealt an unfair hand in life, they stoically resigned

themselves to their lot and made the best of their situation. Ginzo

Murono, his business in Peru taken from him without compensation,

worked at Seabrook Farms until his retirement.

Amazingly, Seiki said he never heard his father complain or display

anger over the injustices he and his family had suffered.

“My father was a saint,” Seiki says. “He never expressed or

showed any kind of bitterness as a result of being interned. In

the end, he was grateful and proud to be an American citizen and

appreciated all the opportunities that this country afforded his

children. He was especially proud of the fact that all his

children received college degrees and went on to have successful

professional careers.”

Seiki does concede that there were occasions in both high school

and college where he was the target of discrimination and racial

slurs directed at him by opposing players.

But his professional career was quite different. “During my

entire 26 years at the Chase Manhattan Bank,” he says, “I was

always treated fairly and with respect and consider it a privilege to

have worked there.”

He notes that the subject of the Japanese internment was never

mentioned in high school, and that during the time he was in college,

very little had been written about the internment. As a consequence,

very few of his classmates or teammates at F & M knew anything

about it. “Most,” he says, “were surprised and shocked to

hear the story.”

Growing up, Seiki said, he was reluctant to discuss the subject of the

Japanese internment, because, “One of my primary objectives was to gain

acceptance, assimilate, and look as ‘American’ as

possible.”

Now, he says, “I am more willing to speak about it. My hope is

that as more is written about the internment experience, it will foster

a greater understanding of the perils of prejudice and discrimination

and lessen the likelihood that these types of injustice are repeated.”

He sums up the way his parents and other Japanese interns dealt with

the difficulties of their lives: "There's a word in Japanese:

gaman – to endure," he says. "My parents used to say that one's ability

to endure hardship prepares one for life."